Which story in your collection required the most drafts or posed the most technical problems?

I worked over the title story pretty hard. For a long while, the ending was different: the question of the absence of children and old people wasn’t given its due. I’d been resisting the very good advice of a fine teacher, who suggested I look at the piece through a more anthropological lens, specifically addressing what was up with everyone in the village being so young and robust. But for a few years I had a particular idea that the story wasn’t at all about family and community but about romantic relationships, sex, and escape. Turns out it was about all of those things. When I allowed myself to explore what had happened, after all, to the kids and oldsters, the ending came naturally and the whole thing just opened wide and settled into itself.

What is your writing process like?

Erratic and undisciplined and chronically behind schedule. To tell you the truth, I’m a mess.

How did you decide to arrange the stories in your collection?

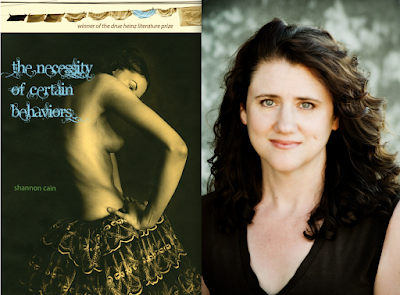

Well, you always put the best one at the end, right? Seriously, it’s not that “Necessity” is the best (they’re all the best) but it seemed to resonate with a lot of people. And I liked it as a title for the collection. “This is How it Starts” seemed to demand to be placed first for obvious reasons, but also because it offers a straightforward introduction to the collection’s obsession with unconventional sexual and romantic behavior. Then there were a couple of stories from a male POV that I didn’t want to place side by side... and the rest was just a question of shuffling and puzzling then shuffling some more.

|

| Nancy Drew, girl detective |

The Nancy Drew series. When I was about 10 years old I began my own Nancy Drew novel, but didn’t get very far because I couldn’t figure out how it would end. Imagine my relief, 25 years later, when I finally took my first writing workshop and learned you don’t need to know where a story is going before you begin it. This was revolutionary news to me. And as I kept writing, and learning, I learned it worked better for me when I even tried to resist this knowing. I often nibble around the edges of an idea for months before I dig into it, but when I find myself writing too much of the plot in my head, I turn my thoughts to something else. I don’t want to give my brain the opportunity to smooth the edges, remove the accidental directions and strange words and weird events that emerge when you’re being an explorer, swept along by the flow. In hindsight it’s clear the Nancy Drew stories were tightly plotted before the various Carolyn Keenes ever put a scene to paper. No surprise that I lost interest in the project. I’ve never been much of a planner.

What kind of research, if any, do you do?

For “The Nigerian Princes,” I hung out on counterscammer websites. (Confession: the emails in that story aren’t my words but found art, a pirated and edited amalgamation of snippets from actual Nigerian scammers.) For “The Queer Zoo,” I spent hours with my nose in the encyclopedic Biological Exuberance: Animal Homosexuality and Natural Diversity, examining naughty pictures of same-sex animals getting it on. For “The Price is Right,” I watched reruns. For “Juniper Beach” I relied on my atlas, of course, and my personal experience as a young Auto Travel Counselor who spent her days assembling actual TripTiks. For “Cultivation,” well: I’ll just say that detailed instructions for growing marijuana aren’t so hard to find on the internet. That’s my story and I’m sticking to it.

If you dabble in any other non-literary forms of expression, what do you do and how does it inform your work?

Lately I’ve been writing a lot about Occupy Tucson, via online articles and blog posts and essays. For the past five years I’ve been working on a novel set in Tucson, where I’ve lived for 30 years. It’s a political story about land use and water and development (and sex and drugs, of course), set amidst the current economic meltdown. So my writings about the Occupy movement couldn’t be more relevant to my current literary expression. This convergence is pretty neat.